The industrial revolution in England (1760 – 1840) was a time of massive economic development impacting every aspect of society. While the benefits were significant and obvious, there was another side that was both tragic, ignored and for many, unknown. Those who were poor, and especially children, were exploited for the social and financial benefit of the better off. The impact on the families of those exploited was devastating, resulting in extreme poverty and associated violence in both behaviour and speech by young and old alike.

Founder of Sunday School

Robert Raikes was born in 1735 and lived in Gloucester, about 150 Km west of London. Little is known of Raikes’ thoughts concerning his life’s work as almost none of his letters and writings have survived. But much is known of his work.

The son of the editor of the local Gloucester Journal, he was educated in the same school that George Whitefield attended some years earlier, St Mary de Crypt Grammar School. At the age of 21 he succeeded his father as editor and ten years later married Anne Trigge. Both he and his wife shared a common concern for the suffering and distressed, particularly of children whom they saw and heard in the proximity of his work.

This was the time of John Howard who in the latter half of the eighteenth century highlighted the atrocious conditions within prisons and was instrumental in initiating prison reform. Robert Raikes shared a similar concern for prisoners and would often visit them and provide support and assistance especially to those whom he considered unjustly treated, and there were many. He continued this prison work for at least 30 years, but it was around the age of forty that his concern expanded to their families, especially the children, who were left to fend for themselves.

It was many years after Raikes began his work with children that a visiting Quaker was taken by Raikes to a particular spot in the city where he was reported to say “This is the spot on which I stood and saw the destitution of the children and the desecration of the Sabbath. I asked myself ‘can nothing be done’ and a voice answered ‘TRY!’ I did try, and see what God has wrought. I can never pass this spot without lifting up my hands and heart to God for having put such a thought into my heart.”

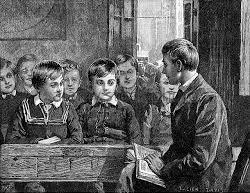

So it was that Raikes determined to try. He began by collecting a group of children on Sundays when the factories were closed (“he had a way with children”) and bringing them to a house in the worst of the slum district where he had arranged for a woman to teach them the Bible. This first attempt in 1781 was not very successful – the children were uncontrollable and the work soon stopped.

Undaunted, Raikes tried again and asked a Mrs. Mary Critchley to be the teacher. Mrs Critchley was a strong-willed and capable woman and despite discouragements, believing that she was wasting her time, she persevered with Raikes encouragement. “We must just try, try and try again” he would say. And Mrs. Critchley did try again, right until she died, whereupon her daughter, Mrs Sarah Packer, took responsibility until she died, then her daughter (Mrs Caroline Watkins) assumed responsibility – 83 years in total.

These meetings were held on Sunday mornings for about three hours. They consisted of teaching the children hymns and Bible stories, and included memorizing Bible verses and parts of the Catechism.

So they persevered.

But, apart from behaviour, the biggest challenge was that the children did not know how to read. So a prerequisite to teaching Scripture was to teach the children to read. But the aim was always to study simple passages of Scripture and learn the Catechism. Raikes’ employment as a printer gave him the opportunity to publish educational material that could be used by his school. His goal was “to plant a seed in the mind … that it may please God at some future period … to bring forth a plenteous harvest.”

Raikes soon started taking these children to church, Pied Piper style, which met with some disapproval and disdain, the children themselves of course having had no experience of church nor any understanding of acceptable behaviour in such austere surroundings.

But he persevered.

Eventually the children adapted to the surroundings, learning and appreciating the regimen of such places, repeating with childish enthusiasm the Lord’s Prayer which affected all present.

It became apparent that children, regardless of their circumstances and background, are spiritually responsive and are open to the redeeming power of the Gospel. One of Raikes’ legacy was to understand and appreciate the spiritual value of childhood.

An effective strategy that Raikes used to promote the work was to encourage public inspection. He gave himself three years from the start of his first School and encouraged others to see for themselves: was there a difference in the streets of Gloucester. And the results were there for all to see. The streets were quieter. Family life had improved. Employers noticed a difference in attitude and behaviour of their child employees. (Child labour was legal until 1833.)

There was, of course, opposition to his work. Just as there was opposition to other current reforms such as slavery and prison conditions, Sunday School was no exception. Church leaders and parliamentarians spoke against the efforts that would “unfit the poor for menial service”. Raikes’ work was deemed “subversive of that order … which constitute the happiness of society … it merits our contempt.” So said the Gentleman’s Magazine of the day. As the work expanded, the Schools were rumoured to be providing children for slavery in the West Indies, of breaking the Fourth Commandment, and of subverting parental rights.

But Raikes persevered.

And others were impressed. Soon Sunday Schools were started in other towns. Deliberately through Raikes’ requirements, and aided by the flexibility of content and structure that he allowed, the work was not exclusive to one denomination and quickly spread. It has been claimed that by 1831 (50 years after the first School) there were 1.2M children attending Sunday Schools. By 1930, the number had grown to an estimated 33M.

At Raikes’ time there was no established public schooling. There were private schools available for those who could afford it, or could access it, but for the poor there was nothing. But such was the success of Raikes’ Schools that in 1811 the English church formed a Society for Promoting Education of the Poor and then eventually in 1833 the English government legislated to provide funding for schools. It was the work of Robert Raikes that provided not just the beginning of the worldwide Sunday School movement, but was the groundwork and incentive for Government funded schooling.

Acknowledgements

- “Robert Raikes Reformer and Roadfinder” by William Goyen, published by the Board or Religious Education, Presbyterian Church of Australia, 1930

- “Men Who Played The Game” by Archer Wallace, published by Allensen & Co. Ltd., 1931

- Various websites

Warren Mack

December 2020